Breathing wildfire smoke isn’t just unhealthy—it can be deadly. DEOHS works with partners across the Northwest to get the word out to those most at risk.

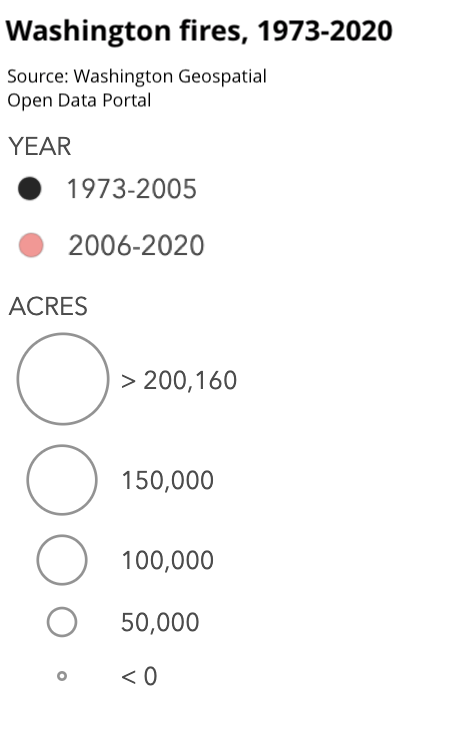

As a former firefighter in Eastern Washington in the 1970s, Kris Ray remembers when a 3,000-acre fire was considered big.

Today, the very nature of wildfires in our region—and the dangerous smoke they emit—is changing dramatically, said Ray, air quality program manager for the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. “Now, 200,000 or a half-million acres is getting way too normal.”

Some 150 miles south, Idanis Cruz’s mother now carries an inhaler to her job picking fruit in the orchards around Mattawa, WA, during wildfire season in case of an asthma attack.

“You’re always kind of scared when summer is coming,” said Cruz, a University of Washington student who has led research on wildfire smoke impacts on farmworkers. “You’re already in the heat, you’re breathing hard and then there’s the smoke. It’s like there’s no escape.”

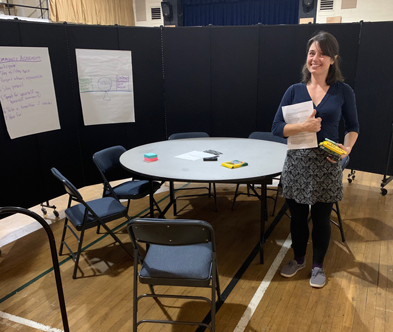

In Western Washington, public agencies and community groups are preparing now for another smoky summer. UW MPH student Joanne Medina recently helped train community leaders in South King County to build box-fan-filter kits to be distributed to residents to improve indoor air quality.

At the training, Medina heard concerns from participants about the health impacts of smoke on vulnerable members of their communities:

How much worse will it be for those already exposed to air pollution from nearby highways?

What about those with underlying respiratory issues like asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or a history of COVID-19?

What else can we do to prepare?

An emerging science

Questions like those are driving the work of nearly a dozen researchers in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) in the School of Public Health. They are at the forefront of an emerging area of science: investigating and communicating about the health risks of wildfire smoke.

DEOHS scientists are currently studying:

Poor health outcomes from exposure to wildfire smoke

Protective measures like HEPA air cleaners or clean air spaces.

The disproportionate impact of smoke on vulnerable people.

Effective ways to get the word out about the health risks.

Through dozens of partnerships across the Northwest, DEOHS is also informing how decision-makers and communities respond to wildfire smoke to protect people’s health.

This spring, DEOHS researchers provided input on a new emergency rule under consideration by the Washington State Department of Labor & Industries to protect workers from exposure to wildfire smoke and similar feedback on proposed wildfire smoke policy in Oregon.

What Are The Risks?

Tiny particles from wildfire smoke can penetrate deep in the lungs

Bigger, smokier fires

Stoked by a changing climate, Northwest wildfires are getting bigger, more intense and more frequent.

“Our fire events have changed over the years, and so have our health risks associated with exposure to the particulate matter they generate,” said DEOHS climate and heat researcher Tania Busch Isaksen.

The tiny particulates that cause the greatest health concern are those 2.5 microns or smaller in diameter (PM2.5). “The PM2.5 concentrations from wildfires in 2020 were an order of magnitude greater than in previous years,” Busch Isaksen said.

These invisible particulates “can bypass the nose and mouth and penetrate deep in the lungs,” said Dr. Coralynn Sack, a pulmonologist and assistant professor in DEOHS and the Department of Medicine. That can trigger oxidative stress and inflammation, and possibly alter immune response.

If you’ve been around wildfire smoke, you’ve probably experienced some of the acute effects, such as headache, itchy eyes, sore throat and cough.

For those with a history of lung or heart conditions, wildfire smoke is linked to more serious impacts, including increased hospitalization and urgent care visits.

Data also links smoke exposure to acute cardiovascular impacts such as heart attacks, arrhythmias and strokes, Sack said—as well as an increased risk of mortality, as DEOHS researchers showed in a 2019 study.

Our new normal

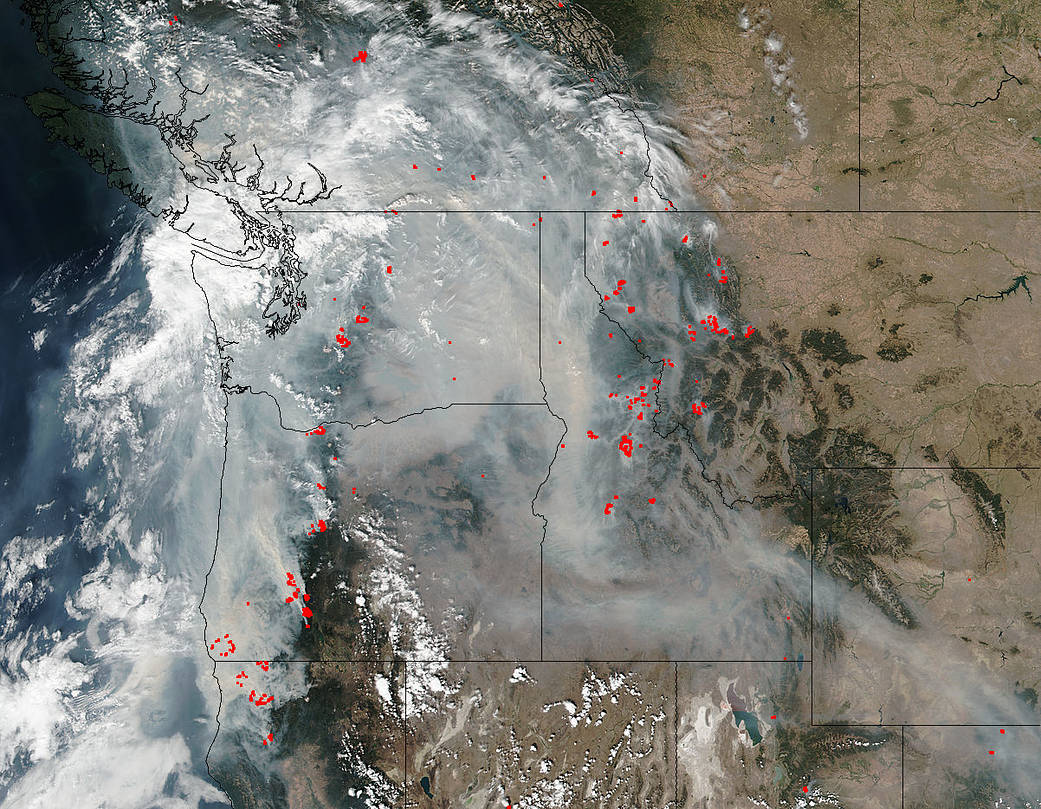

In 2017, Washington seemed to cross an invisible threshold when the threat of wildfires and smoke became a regional phenomenon in what some are calling a new “fifth season” in the Northwest.

It was the year of “our collective awakening as a state,” said Nicole Errett, a DEOHS disaster and health policy researcher.

That September, dozens of wildfires raged across the Western US, creating a statewide smoke event that prompted Washington’s governor to declare a state of emergency.

Errett and Busch Isaksen were in a car enroute to a conference on climate change that month. The two would go on to form a research partnership called the UW Collaborative on Extreme Event Resilience. Both are also members of the UW Center for Health and the Global Environment.

On the drive, they joined a conference call with local health officials to talk about the wildfire smoke smothering the state. Health officials were looking for support as they worked to create consistent public health messaging about what people should do to protect themselves.

Getting The Word Out

While wildfire smoke affects us all, the impacts hit some groups harder than others.

Becoming a team

With funding they learned about at the conference, Errett and Busch Isaksen hosted a wildfire smoke risk communication symposium in 2018 that drew more than 70 people representing government agencies, academia, tribes, communities and public health practitioners to Seattle to talk about smoke messaging and the state of the science.

“It created a lot of momentum and really brought people together around how they could address smoke in their own context,” Errett said. “We became a team working on these issues.”

That partnership approach has proven critical in reaching people with timely information about the health risks of wildfire smoke.

“We’re dedicating an increasing amount of time to wildfire smoke,” said Julie Fox, ambient air epidemiologist for the state Department of Health (DOH). “We need to help others be the messengers” by aligning efforts among other agencies and partners.

.jpeg)

Fox got help from a DEOHS MPH student, Kaitlyn Kelly, to help create uniform messages about smoke and public health. Kelly now works at DOH as the state’s air quality policy specialist.

Fox also launched a statewide Wildfire Smoke Impacts Advisory Group in 2018 that developed a risk communications toolkit about the dangers of breathing wildfire smoke. Busch Isaksen serves on the group. DOH also developed multilingual resources on air quality and health recommendations.

“We know the risk is real,” Busch Isaksen said. “Each year, we’re getting a clearer picture of what the health effects are. And it’s important to communicate that just as clearly.”

Tailored public health messaging about reducing smoke exposure may encourage behavior changes like limiting outdoor activity during smoke events, according to a recent study of bike and pedestrian activity in Seattle by DEOHS alumna Annie Doubleday, Youngjun Choe, Busch Isaksen and Errett.

Reaching the hard-to-reach

While wildfire smoke affects us all, the impacts hit some groups harder than others.

They include children, the elderly, pregnant women, farmworkers and others who work outdoors, as well as people without access to permanent shelter and those already disproportionately burdened by hazardous environmental exposures because of where they live.

“Those folks end up having to bear the brunt of environmental hazards, and they often don’t have the same voice or power to make change,” Errett said.

Cruz, the UW student, grew up in Mattawa watching summers get increasingly smoky and hearing stories from her parents and other local farmworkers about the wildfire smoke that would blanket the orchards where they worked.

Cruz is also a research coordinator with the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center, part of DEOHS, which recently launched a wildfire smoke safety page for farm and forestry workers.

Cruz led a small UW research study in 2018 that found nearly 3 out of 4 Mattawa farmworkers reported being exposed to an unhealthy amount of smoke on the job.

All participants said they lacked information on how to protect themselves. Most tied bandanas around their faces, sometimes two at a time. Fewer than half reported wearing a mask.

“A lot of them knew or assumed smoke was dangerous, but they didn’t know what to do about it, and they weren’t getting that information in the workplace,” Cruz said.

Wenatchee CAFE, a DEOHS community partner, is one of the organizations reaching out to farmworkers and other Latinx community members in Central Washington with health information about wildfire smoke.

“We discovered there’s a big need for information, a need for people to know about evacuation plans, emergency preparedness and about the impact of these fires and the smoke on our bodies,” said Alma Chacón, CAFE’s executive director.

Hear more from Laura Rivera, CAFE’s environmental justice coordinator, about her work with Latinx families

Becoming Smoke-Ready

Experts say a system to clean indoor air is just as critical as having a smoke detector

Surviving and thriving

Elizabeth Gribble Walker hunkered down with her 4-year-old and newborn for 10 days without power during the 2014 Carlton Complex fire in Washington’s Methow Valley—at that time, the largest wildfire in state history. The smoke was thick and oppressive, and the fast-moving fire made her worried for their safety.

“Unfortunately, that summer is becoming the norm rather than the exception,” she said recently. Last summer, wildfire smoke made air in the valley unhealthy to hazardous for nearly two weeks, and in 2018, those conditions persisted for over a month.

A DEOHS affiliate assistant professor and PhD alumna, Walker had recently taken the helm of a community organization now known as Clean Air Methow. At the time, it focused on helping the community handle poor winter air quality. Many residents heat their homes with wood, and atmospheric temperature inversions trap the smoke.

After the Carlton Complex fire, Walker expanded the group’s mission to include wildfire smoke as well.

“We need to help people survive and thrive,” she said.

Now she and her team, who partner regularly with DEOHS researchers and others, preach the gospel of clean indoor air.

To drive home the point, she has brought handheld air quality monitors into homes and schools during wildfire smoke events.

“People were shocked and horrified that indoor air quality was as bad as it was,” she said.

Taking care of indoor air

During smoke events, hazardous levels of PM2.5 can accumulate inside homes, especially when people open windows at night to cool off.

Having a system to clean indoor air is just as critical as having a smoke detector, Walker said. The best options include adding a filter with a high MERV rating, such as MERV-13, to a central air conditioning system, or getting a portable HEPA air cleaner, which can cost $100 or more.

For a cheaper but still highly effective option, you can attach a MERV-13 furnace filter to a box fan. In Walker’s tests, such box-fan filters (about $40) can bring hazardous indoor air to safe levels within about 15 minutes in a small bedroom.

On the Colville Reservation, Ray worked with tribal members to produce a video on how to build a box-fan filter. It’s part of the team’s efforts to provide culturally appropriate resources for smoke season on the reservation, which spans 2.8 million acres.

Like the Methow, parts of the reservation experience unhealthy air in both winter and summer. “We’re trying to do everything we can to get people to minimize that exposure,” he said.

As wildfire smoke increasingly threatens the entire Northwest, “air filtration in your home is even more important because you probably don't have any place to go,” Ray said.

Box-fan filters in the city

Box-fan filters fill a need in urban areas too, where many vulnerable residents can’t afford a HEPA air cleaner and community clean-air shelters are less available because of the pandemic.

In South King County, five community-based organizations will distribute free kits to 400 community members this summer through a program sponsored by Public Health — Seattle & King County and the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency.

Organization leaders welcomed “this opportunity for community residents to create their own clean air in their own living spaces,” said Medina, the MPH student in environmental health at DEOHS who is training leaders and evaluating the program for her practicum.

Protecting body and mind

Building resilience in the face of wildfire smoke is a key focus for researchers and community groups. In 2019, Anna Humphreys, then a student in the UW Schools of Public Health and Social Work advised by Walker and Errett, researched concerns about smoke season among Methow Valley residents.

She worked with DEOHS’s Interdisciplinary Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics and Environment (EDGE) to design a pamphlet with recommendations for staving off anxiety, depression and lethargy during smoke events.

This year, Clean Air Methow and the EDGE Center collaborated to create a series of podcasts called “The Fifth Season,” in which locals share their stories of smoke resilience.

Community members in the valley are also helping to collect better data. Walker, together with Errett and then-DEOHS undergraduate Amanda Durkin, launched the Clean Air Ambassadors program in 2019.

The group of more than 25 volunteers host clean-air sensors at homes, businesses, municipal buildings and schools, with the data generating a real-time air quality map that offers more detail than the two Department of Ecology sensors in the 60-mile-long valley.

“You can move just a few miles and experience very different air quality,” Walker said. People use the map to plan for breaks from sheltering indoors, such as taking a walk in an area with cleaner air.

Methow Valley air quality map

UW steps up on climate change

Summer fire season in the Northwest is ramping up quickly, with Gov. Jay Inslee declaring a wildfire state of emergency this week fueled by drought and record-breaking high temperatures.

"Climate change is no longer referred to as a slow-moving disaster,” Busch Isaksen said. “We are seeing the impacts in real time. We can no longer ignore the effects we've had on our earth systems and the consequences to our health."

The UW is helping to lead the way in responding to climate change. “We’re using UW resources to meet real-time community needs,” Errett said. “It shows the University can be a huge partner as we adapt to climate change and fill in the gaps.”

“As an anchor institution in the state, we really are trying to step up to meet that demand.”

How to protect your health before and during wildfire smoke events

Know the air quality: Check the Washington Smoke blog or Washington Department of Ecology for real-time air quality information to determine whether it is safe to be outside.

Clean your indoor air: Get a portable HEPA air cleaner (use these tips to choose one), build a box-fan air filter, or run your air conditioning on recirculation with an upgraded filter (MERV 13 is best).

Wear a mask: If you must be outside in poor air quality, wear a NIOSH-approved particulate respirator, such as an N95 mask, that is well-fitted and worn properly.

Credit: Adapted from Clean Air Methow.

More resources

- Washington Smoke blog

- Smoke from fires by the Washington State Department of Health

- How to create a clean air room at home from the US EPA

This special feature produced by the DEOHS communications team: Veronica Brace, Jolayne Houtz, Deirdre Lockwood, Nick Nemetz.

Podcast from "The Fifth Season" by UW EDGE Center, UW Communication Leadership Program and Clean Air Methow.

Images (top to bottom): Courtesy of UW Photo Collection, USDA Photo Archives, Alamy and Soo Ing-Moody.