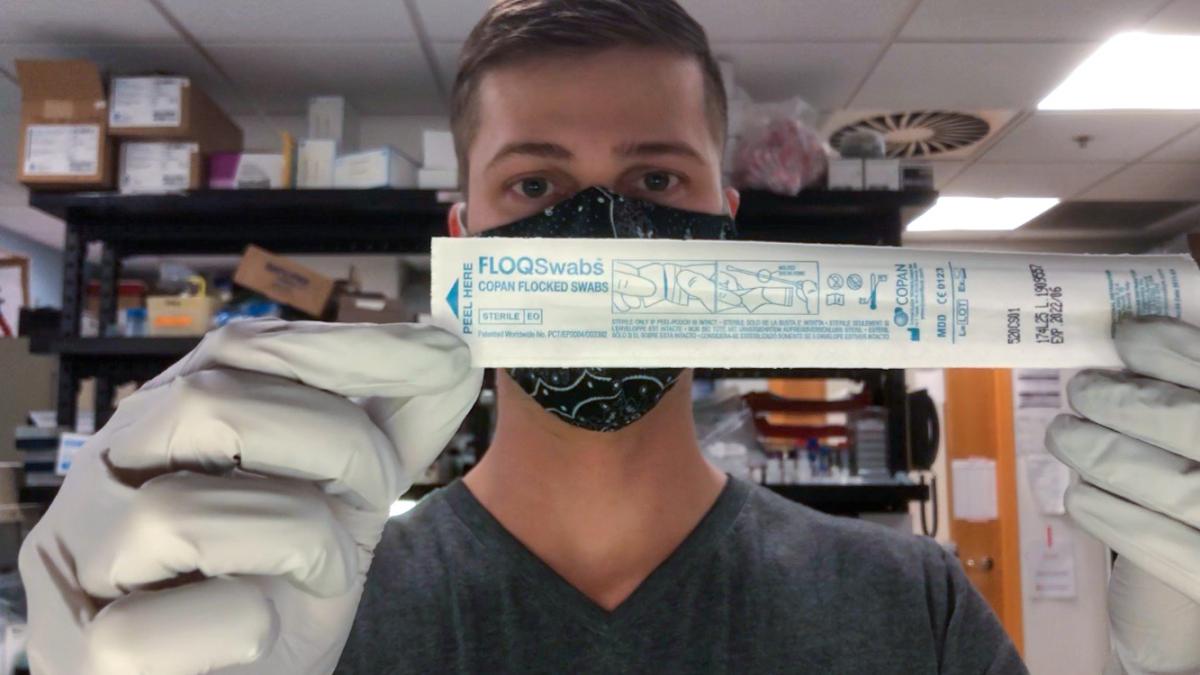

DEOHS master's student Grant Whitman in Professor Jerry Cangelosi's lab with one of the swabs he is evaluating to make TB diagnosis faster and more efficient. Photo: Courtesy of Whitman.

It’s one of several innovative ideas to help end TB from the research lab of DEOHS Professor Jerry Cangelosi

The world has pledged to end tuberculosis (TB) by 2035.

COVID-19 threatens to move the goalposts.

In Jerry Cangelosi’s lab at the University of Washington—as in many labs and clinics around the world—efforts are being pulled from TB into COVID-19 research and diagnostic testing in response to the global pandemic.

“Could COVID be driving increases in undetected TB cases? This is something we worry about in TB research,” said Cangelosi, DEOHS professor. “That could jeopardize our progress toward ending TB.”

Now Cangelosi’s research team and partners are launching clinical studies of a potentially game-changing idea: What if a single test could detect both diseases simultaneously?

That’s one of several innovative TB research studies Cangelosi and his lab team are pursuing to improve screening and detection of one of the world’s top infectious disease killers.

In recognition of World TB Day today, here are updates on three of the team’s TB and COVID-19 research projects.

Using tongue swabs to detect TB and COVID-19

There are many similarities between TB and COVID-19. Both are respiratory pathogens, and patients experience many of the same symptoms, including fever and cough.

Cangelosi, along with DEOHS Research Scientist Rachel Wood and partners in South Africa, have already proven that an oral swab can be used to detect TB.

That’s a big improvement from the current practice of health care workers collecting sputum coughed up from deep within a person’s lungs—messy, difficult work for patients and a potential health risk for workers.

Separately, Cangelosi has worked with a different team to show that oral swabs can be used to diagnose COVID-19.

This month, Wood and Cangelosi are working with the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative at the University of Cape Town and other partners to launch a clinical trial using tongue swabs to test for both TB and COVID-19 at the same time.

“It’s looking like we can get good detection for both with methods that are going to be a lot easier and safer and faster in the lab and potentially less expensive,” Wood said.

The method will be tested first in health clinics and subsequently in people’s homes, with samples collected by the patients themselves under supervision of a health care worker.

For Wood, who began working on the concept of oral swabs for TB testing in 2013 as a DEOHS master’s student, it’s exciting “to think that something you worked on can make people’s lives better, get them into treatment sooner. I have really high hopes.”

The project is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Testing TB self-sampling with health care workers

The design of the TB-COVID study is informed by separate research that DEOHS master’s student Renée Codsi is leading on the attitudes of South African health care providers toward oral swabs and supervised self-sampling for TB.

Her work examines health care providers' willingness to use tongue swabs in the clinical setting and during patient home visits.

Codsi is creating guidelines for provider sampling and supervised self-sampling methods for TB. The research became even more urgent as the COVID-19 pandemic swept the globe.

Initially, health care workers liked the ease of collecting oral swabs instead of sputum. But with COVID-19, “they were freaked out. They didn’t want to stand there right in front of the patient who is saying ‘ah’ and sticking out their tongue when they could have COVID, TB or both,” she said.

“So we thought, what if it was supervised self-swabbing by the patient?” said Codsi, who plans to graduate this spring with her MPH in One Health.

She worked with DEOHS Assistant Professor Nicole Errett to design the study and analyze the data.

Codsi modeled part of the idea after the Husky Coronavirus Testing program at the UW, where health care providers stand behind a plexiglass shield wearing personal protective equipment.

They hand the swab to the patient and provide instructions on how to swab their own nose, sometimes using a large diagram to help illustrate the steps. The patient then places the swab into a tube held by the health care worker.

Codsi plans to continue working on the idea as a newly admitted PhD student in DEOHS starting next fall. This project is also funded by the Gates Foundation.

Making TB diagnosis faster, more efficient

To reach the international goal of ending TB by 2035, the World Health Organization (WHO) calls for diagnosing and treating 40 million people with TB by 2022. Oral swabs could make that goal a lot easier to reach.

But first, the swabs need to be compatible with the automated molecular testing systems used in most health care settings to detect TB.

DEOHS master’s student Grant Whitman worked with Cangelosi and Research Scientist Kris Weigel to develop new sampling, storage and extraction protocols so that the swabs will work with GeneXpert Ultra, a disease diagnostic platform recommended by WHO for the rapid detection of pulmonary TB.

It most often uses sputum analyzed with a cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test to detect the DNA in TB bacteria.

Whitman found that using two patient samples collected with a specific type of oral swab makes the swabs compatible with GeneXpert and comparable in sensitivity to previously reported manual methods.

The new method will go into clinical studies this month in countries in Africa and Asia, led by research collaborators at the University of California, San Francisco, and another group led by researchers at Stellenbosch University in South Africa.

Because of his work on the method, Whitman recently won a $2,000 junior investigator award from the Tuberculosis Research and Training Center at the University of Washington.

“Seeing something go from the lab to the clinic is a humbling experience,” said Whitman, who has been working on the project for 18 months. He plans to graduate this spring with his MPH in Environmental and Occupational Health and hopes to continue in infectious disease research.

“This is an opportunity to reach more people, collect samples faster and do it in a way that is safer for clinicians,” he said. The project is funded by the National Institutes of Health.